I’m excited to join this event with colleagues from around the world on November 25th 2020, 10:00 –17:00 (UK BST), and I thought I’d share it here to invite others to join.

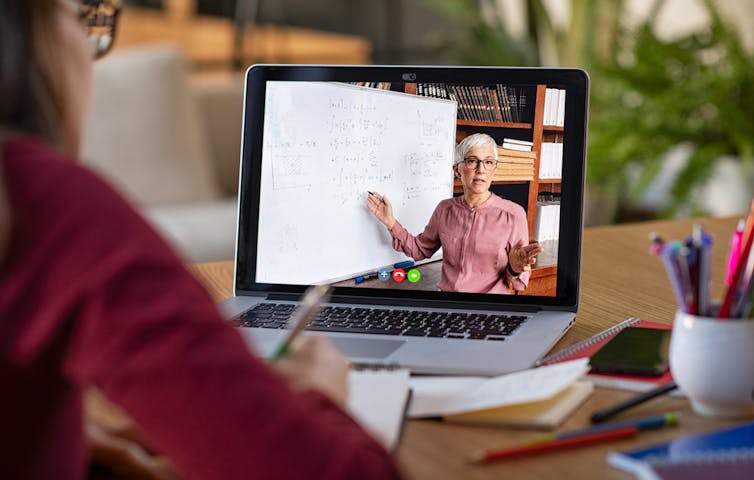

That Higher Education is in a period of transformation is a moot point. The COVID:19 pandemic has resulted in a period of rapid digital transformation for universities all around the globe. However, this rapid change has created positive and negative effects on student learning and experience, and some changes will be short-lived and others long-lasting.

The purpose of this symposium is to explore this transformation from the perspective of existing and on-going research in digital education, to help the higher education sector to set a direction of travel which creates positive effects on access to higher education and enhanced student learning, through long-lasting changes. The symposium will cover topics relating to online education, open education, blended and hybrid learning, learning data and its impacts, digital skills and lifelong learning.

The symposium will hear from global experts in digital education about their experiences of digital transformation in higher education and related sectors, and gather their views about the most appropriate courses of action to create sustainable, accessible, inclusive, quality higher education to support lifelong learning for all.

To register for this free, online, event please visit:

Speakers:

Simone Buitendijk, Vice-Chancellor, University of Leeds

Laura Czerniewicz, Director: Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching (CILT), University of Cape Town

Josie Fraser, Head of Digital Policy, Heritage Fund UK

Michael Gallagher, Lecturer in Digital Education, Centre for Research in Digital Education, University of Edinburgh

Vitomir Kovanovic, UniSA Education Futures, Australia

Allison Littlejohn, Director of University College London’s knowledge lab, University College London

Neil Morris, Dean of Digital Education, University of Leeds

George Veletsianos, Canada Research Chair in Innovative Learning & Technology, Royal Roads University, Canada